As the international Passive House standard has spread from Germany to all corners of the world, questions inevitably have arisen over how well this standard applies to climates that differ from Germany's cool, temperate one. The Passive House Institute (PHI) has devoted significant research to this question and made adjustments when necessary, such as adapting the classic PH standard to account for additional demand for dehumidification in humid climates. Many other institutions and organizations have contributed extensive research to the design and construction of very low-energy buildings for a range of climate types. In several countries, tailored Passive House requirements have been developed in response to concerns about the climate specificity of the international PH standards.

Regardless of these concerns, an understanding of Passive House principles, which are solidly rooted in building physics, is critical to the construction or retrofit of high-performance buildings. Indeed, as the PH approach has spread globally, it has transformed the conversation about what is possible to achieve with a high-performance envelope. The Passive House buildings constructed in diverse climate types—especially those that have been monitored and whose results have been published—provide irrefutable evidence of this approach's success. That said, almost any PH project—particularly those designed by novice PH practitioners—can be viewed to a certain extent as a building science experiment, and practitioners with the most experience in a given climate offer valuable insights for new designers.

Mediterranean Climate Solutions

Micheel Wassouf, a certified PH designer from Barcelona, Spain, presented monitoring results from two PH residences in his region at the 2015 International PH Conference to address doubts about the suitability of Passive House for the Mediterranean summer. One project was a retrofit of a small row house originally constructed in 1918 and located in northern Barcelona. The retrofit, planned and led by architects from Calderon Folch Sarsanedas, involved adding insulation to walls, roof, and floor slab, and installing new high-performance, low-emissivity windows, including a skylight with a south-western orientation to increase winter solar gains. Heating demand dropped dramatically from 171 kWh/m²a to just 17.5 kWh/m²a; remarkably, the house had no air conditioning yet maintained comfortable temperatures.

Similar comfort results were reported by architects Josep Bunyesc and Silvia Prieto at the 2015 PHI conference based on their monitoring of five PH residences in northeastern Spain—two in Lleida and three in the Pyrenees. They concluded that for both new builds and retrofits, Passive House should be compulsory or at minimum the standard that clients demand for their comfort, economic benefit, and the Earth's well-being. As architects who have employed the PH method since 2009 and witnessed its impressive results, they stated they would find it morally impossible to revert to other design approaches.

Adapting to Mixed Humid Climates

Adam Cohen, an experienced PH designer and builder in Virginia, has been at the forefront of adapting Passive House principles to mixed humid climates. He has achieved many PH firsts in the United States, including the design and construction of a large assembly building with a commercial kitchen inside the thermal envelope and, more recently, a dental clinic.

According to Cohen, the most crucial consideration in these climates is limiting direct solar gain, especially during transitional seasons when overheating can become a significant problem. An energy recovery ventilator (ERV) to reduce moisture entering the building is essential, as is installing a pre-cool and pre-dehumidify loop on the ERV to lower the incoming latent and sensible load. Finally, building occupants need education about managing interior heat gains during the hottest months by activating non-automated shading systems and possibly limiting prolonged cooking or plug loads, as Passive House buildings retain heat and night cooling in humid climates often isn't practical.

Milder Climate Considerations

In milder climates, where space conditioning loads can be minimized through a Passive House envelope, different challenges emerge. Combining ventilation and space conditioning distribution systems can create space-saving advantages. However, since space conditioning typically requires higher air flows than ventilation, this strategy presents inherent challenges.

One Sky Homes, a California design/build company, has experimented with innovative solutions. In their Sunnyvale house retrofit, they installed both a heat recovery ventilator (HRV) and a mini-split heat pump that together supply fresh air and conditioned air to common areas. Rather than ducting either appliance, the hallways function as supply plenums to transport air to bedrooms. Continuously operating low-volume exhaust fans with efficient electronically commutated motors (ECMs) help draw the fresh, conditioned air into bedrooms. Monitoring of indoor air quality and energy use has confirmed this strategy's effectiveness.

Moisture Management in Rainy Regions

In rainy areas, such as the Pacific Northwest region of the United States, bulk water management becomes a critical issue for all buildings, including Passive Houses. A vented rain screen, which provides a channel where bulk moisture can drain or evaporate, positioned just inside the exterior siding serves as a key detail in these areas. Passive House practitioners have become adept at combining this feature with the required exterior insulation.

A common exterior wall assembly in these regions includes, from outside to inside, exterior siding, a vented rain screen gap created by battens that hold in place a weather-resistant barrier over exterior insulation, and finally the stud wall. Some builders have used wax-impregnated exterior sheathing, as it can function both as a weather-resistant barrier and an air barrier when its joints are thoroughly sealed.

Climate-Specific Mechanical Ventilation

The mechanical ventilation system must be designed with the local climate in mind. In colder climates, the heat recovery efficiency of an HRV should be at least 80 percent, while in cool temperate climates, the minimum efficiency can drop to 75 percent. Additionally, using an ERV may be necessary in colder climates to maintain acceptable indoor humidity levels during winter, as the fresh outdoor air typically has very low humidity.

In very mild climates, where windows can remain open nearly year-round, questions sometimes arise about mechanical ventilation's necessity. A recent study in areas of New Zealand with mild climates examined this question in 15 houses across three climate zones. These buildings were tested for airtightness and indoor contaminant levels. The findings revealed that even very leaky homes did not guarantee good indoor air quality, as contaminant levels depended significantly on daily wind conditions. This study confirms what many others have observed: random leaks in a building envelope provide no guarantee of healthy indoor air quality.

Indoor Air Quality Considerations

In all climates, indoor air quality must be actively addressed. Even with constant mechanical ventilation bringing fresh air into a Passive House structure, all indoor air quality concerns may not be resolved. In airtight homes, using less toxic building materials becomes increasingly important, especially for materials with the largest indoor surface area, such as flooring throughout a residence.

When using engineered wood, consider products that are either low in formaldehyde or formaldehyde-free for both flooring and cabinets. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) maintains a list of compliant wood products; research has shown that choosing these products can reduce indoor formaldehyde levels by more than 40 percent.

Kitchen ventilation presents particular challenges in Passive House residences. While the PH approach assumes extraction of air from the kitchen area, it doesn't necessarily specify a range hood. However, research indicates this approach may lead to poor indoor air quality, depending on the mechanical system design and whether the cooktop is gas-fueled, electric, or induction.

For optimal extraction of cooking-related pollutants—both combustion byproducts and particles and chemicals generated during any cooking process—a range hood centered over the stove, covering all burners, and providing 100 to 200 cubic feet (2.83–5.66 m³) per minute of targeted ventilation is advisable. Flat-bottomed hoods are less effective at capturing pollutant plumes compared to more conical-shaped designs. Commissioning ventilation systems after installation and performing regular maintenance are critical for ensuring proper function, and occupants often need education about system operation.

No matter the climate type, examples now exist worldwide demonstrating successful implementation of Passive House principles. The global adoption of these principles continues to grow, proving that with proper adaptation and understanding of local conditions, Passive House design can deliver exceptional comfort, health benefits, and energy efficiency in virtually any climate on Earth.

Ankeny Row: Cohousing for Seasoned Folks in Portland

How a group of baby boomers created a Passive House cohousing community in Portland, Oregon, that addresses both environmental sustainability and the social needs of aging in place.

Evolving Passive House Standards: Adapting to Climate and Context

Explore the evolution of Passive House standards from the original 'Classic' model to climate-specific certifications like PHIUS and EnerPHit, reflecting a growing need for flexibility and global applicability.

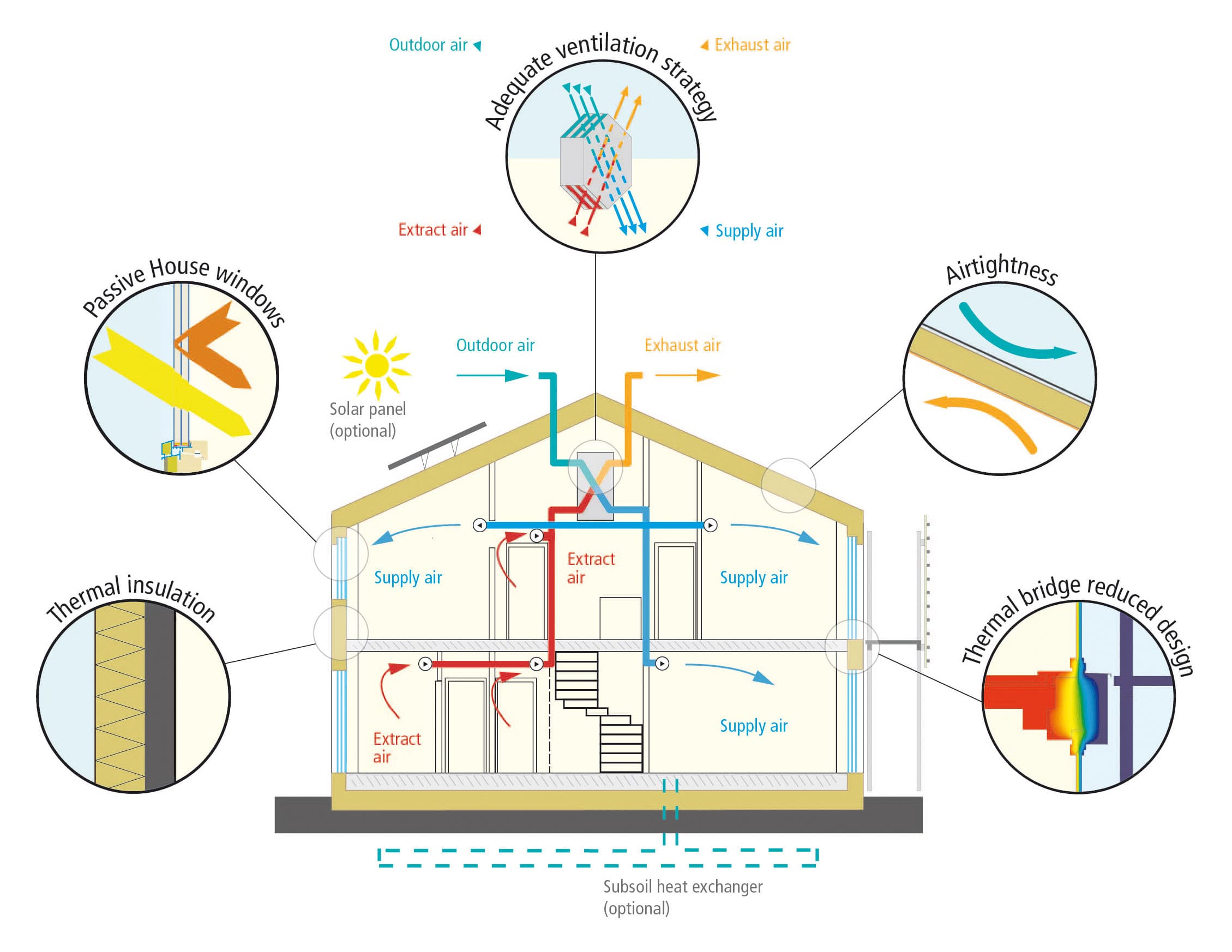

Seven Principles of Passive House Design: Building for Efficiency and Comfort

Explore the seven foundational principles of Passive House design that ensure superior energy efficiency, exceptional indoor air quality, and lasting comfort in every climate.